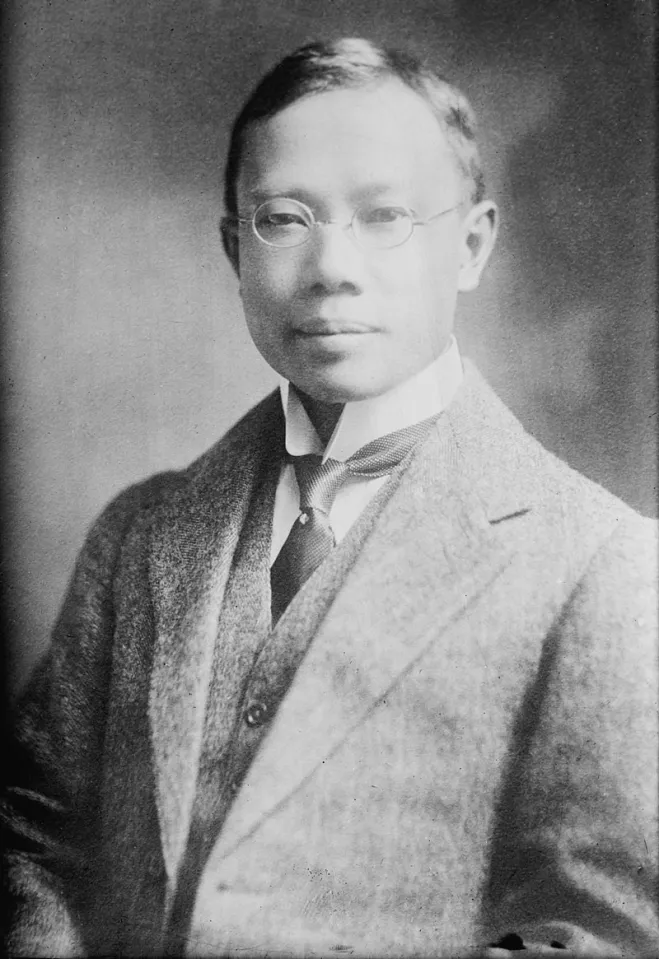

Early Life and Education of Wu Lien-teh

Wu Lien-teh, born on March 10, 1879, in Penang, Malaysia, is remembered as a groundbreaking epidemiologist and a pioneer in global public health. He was born into a large family, with four brothers and six sisters, and raised by a father who had immigrated from China and worked as a goldsmith.

Wu’s academic potential became evident early on. He attended the Penang Free School before earning the prestigious Queen’s Scholarship, which paved his way to study medicine at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, in 1896. This made Wu the first student of ethnic Chinese descent to attend the university.

His medical training continued at St Mary’s Hospital in London, followed by stints at other leading institutions, including the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, the Pasteur Institute in Paris, Halle University in Germany, and the Selangor Institute in Malaysia. This diverse education gave Wu a unique and global perspective on medicine.

The Start of a Medical Career

Wu returned to Malaysia in 1903 and married Ruth Shu-chiung Huang, the daughter of Chinese revolutionary and educator Wong Nai Siong. That same year, Wu began his medical career at the Institute for Medical Research in Kuala Lumpur, becoming the first research student at the institution.

In 1907, Wu and his family moved to China, where his medical journey would gain international attention.

The Manchurian Plague and Wu’s Groundbreaking Work

In 1910, Wu was called upon by the Chinese government to investigate a mysterious and deadly disease that was sweeping through Manchuria and Mongolia. This illness turned out to be pneumonic plague, a highly contagious and airborne form of the disease.

Wu determined that the plague was spreading through respiratory droplets, a revolutionary insight at the time. His understanding of airborne transmission led him to develop a new type of protective mask. Unlike the thinner surgical masks previously in use, Wu’s design included multiple layers of gauze and cotton for effective filtration. This innovation is considered the prototype of modern medical face masks, including today’s N95 respirators.

To combat the epidemic, Wu implemented a multifaceted strategy:

- He ordered the immediate quarantine of infected areas.

- Temporary hospitals were established to treat and isolate patients.

- Disinfection of buildings and restrictions on public gatherings were enforced.

- He oversaw the cremation of plague victims, which was controversial at the time but proved effective in controlling the spread.

These efforts helped to end the Manchurian plague by 1911, saving countless lives. Wu’s scientific approach and administrative rigor earned him global recognition.

Recognition and Nobel Prize Nomination

In 1935, Wu Lien-teh was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, making him the first Malaysian to receive such an honor. Although he did not win, the nomination highlighted the global importance of his contributions to medicine and epidemiology.

Wu’s legacy in controlling airborne diseases was again acknowledged during the COVID-19 pandemic, when historians and health experts reflected on his early work. His innovative face mask design became a reference point for understanding the evolution of personal protective equipment.

A Life of Service in China

Beyond his work during the Manchurian plague, Wu continued to shape the future of public health in China. In 1908, he was appointed vice director of the Army Medical College. In 1915, he founded the Chinese Medical Association, the country’s oldest and largest non-governmental medical organization. His contributions laid the foundation for modern Chinese medicine and public health policy.

Wu also played a vital role in combating the cholera pandemic that struck northeast China in 1920. His strategies—ranging from isolation of patients to water sanitation—were based on science and experience, further establishing his reputation as a visionary epidemiologist.

Turmoil and Return to Malaysia

Despite his many accomplishments, Wu’s life was not without challenges. During the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931, Wu was detained on suspicion of being a Chinese spy. Although he was eventually released, the Japanese occupation forced him to flee China and return to Malaysia.

There, he continued to contribute to medicine and public health until his death in 1960 at the age of 80. His devotion to medicine and humanitarian work remained steadfast throughout his life.

The Legacy of Wu Lien-teh’s Face Mask

Wu’s face mask design was instrumental during the 1910-11 Manchurian Plague and remained a model for future epidemics. When the Spanish flu swept across the globe in 1918, Wu’s mask became widely recognized among scientists and medics as a symbol of effective prevention.

The legacy of Wu’s mask reached a new generation during the COVID-19 pandemic. The N95 mask, which became standard for protecting healthcare workers and the public, is widely considered to be a direct descendant of Wu’s pioneering design. As nations struggled with mask mandates and shortages, many scholars and health professionals cited Wu’s early 20th-century work as a cornerstone of infectious disease control.

In 2021, Google honored Wu with a Doodle on what would have been his 142nd birthday, writing: “Wu’s efforts not only changed public health in China but that of the entire world. Happy birthday to the man behind the mask, Dr. Wu Lien-teh!”

Who Was Ruth Shu-chiung Huang?

Ruth Shu-chiung Huang, the wife of Wu Lien-teh, was herself born into a prominent and politically active family. She was the daughter of Wong Nai Siong, a Chinese revolutionary and educator known for his role in promoting reform and education during a turbulent era in Chinese history.

Ruth’s sister was married to Dr. Lim Boon Keng, a reformist doctor who played a key role in promoting health and educational advancements in Singapore. This interconnected network of reformers and scholars created a family environment dedicated to progress and service.

Wu and Ruth were married in 1903 and relocated to China in 1907 as Wu took on greater responsibilities in the public health sector. Tragically, Ruth died not long after the move, marking a profound personal loss for Wu during a critical period in his career.

The Tragedy of Loss: Wu and Ruth’s Children

Wu and Ruth had three sons together. Unfortunately, while the family lived in China, two of their children passed away. This double tragedy added another layer of sorrow to Wu’s life and perhaps deepened his sense of mission in the medical field.

The loss of his wife and two children did not deter Wu from his calling. Instead, he continued to dedicate himself to fighting diseases and improving healthcare systems, turning personal grief into a life of public service.

Wu Lien-teh’s Enduring Influence

Wu Lien-teh’s work has had a lasting influence on the global health community. His emphasis on preventive measures, public education, and scientific integrity shaped early 20th-century public health responses and set the stage for modern epidemiology.

His contributions have been recognized in various ways:

- The World Health Organization and scholars regularly cite his work in discussions about pandemic preparedness.

- His autobiography, Plague Fighter: The Autobiography of a Modern Chinese Physician, provides valuable insights into the early development of medical science in Asia.

- Several academic institutions and medical organizations continue to honor Wu’s legacy through lectures, awards, and research grants.

Conclusion: Remembering the Man Behind the Mask

Wu Lien-teh’s story is one of resilience, innovation, and humanitarianism. From humble beginnings in Penang to global recognition as a pioneer in epidemic control, Wu’s life and legacy remain a beacon of inspiration for scientists and public health workers today.

His invention of the surgical mask, leadership during deadly epidemics, and foundation of vital medical institutions highlight his importance not just to China or Malaysia, but to the world. His wife Ruth, though often overlooked in historical accounts, was part of a reformist family that shared his values and aspirations.

Together, their story reminds us that the fight against disease is both a scientific and deeply human endeavor—fueled by loss, love, and the enduring pursuit of knowledge.

- Chris McCausland takes a break from Strictly on romantic walk with rarely seen wife after samba row - June 4, 2025

- Popular THC Seltzers in Michigan Right Now - May 31, 2025

- Arizona’s Most Popular THC Infused Drinks - May 31, 2025