Social Status and Marriage

Marriage Laws

Marriage laws in Ancient Egypt were highly complex and regulated by various decrees issued by the pharaohs. In terms of women’s legal rights, ancient Egyptian marriage laws granted certain privileges to women, particularly those from wealthy families.

The most significant aspect of these laws was the concept of “ma’at,” which referred to social balance and order. Ma’at was considered essential for maintaining harmony in society, including within marriage relationships.

Women from upper-class families enjoyed relatively more rights than their lower-class counterparts. They could own property, engage in trade, and participate in public life, although these activities were often restricted by the patriarchal nature of Egyptian society.

The code of Hammurabi, a Babylonian law code that influenced Egyptian laws, recognized women’s right to initiate divorce proceedings. However, this privilege was usually reserved for women who were married to men from lower social classes.

Some marriage contracts, known as “marriage papyrus,” allowed women to negotiate the terms of their marriage and even specify the conditions under which they could initiate a divorce. These papyri often reflected the woman’s status and the family’s wealth.

Ancient Egyptian laws granted men significant control over their wives’ lives, including the right to administer their property, manage their business dealings, and discipline them for misbehavior. However, these rights were not absolute, and some cases of domestic violence led to severe penalties for perpetrators.

Despite these regulations, women’s rights in marriage remained relatively limited throughout ancient Egyptian history. Women were often expected to prioritize their roles as wives and mothers above all else, although this did not preclude them from engaging in other activities or possessing personal property.

The influence of Greek and Roman cultures on Egyptian society during the Ptolemaic period led to further changes in marriage laws, including increased emphasis on the role of women as citizens. However, even under these new influences, women’s rights remained subject to various restrictions.

Women could marry at the age of 1214, men at 15.

In Ancient Egypt, women’s legal rights were largely limited and influenced by their social status and relationship with men.

The law codes of the time, such as those compiled by Pharaoh Horemheb around 1323 BCE, show that a woman could be married at the age of 12 or 14, while boys typically reached marriageable age at 15.

Marriage was often arranged by families for economic or social gain, and women had limited control over their own lives and choices within the household.

One notable example is the “Instruction of Ptahhotep,” a wisdom text from around 2400 BCE that advises men to treat their wives with respect and kindness.

The “Edict of Horemheb,” however, suggests that women could own property and participate in business dealings, although this may have been more common among wealthy and educated women.

Some female officials, such as the Vizier’s wife, held important roles in government, but their responsibilities were largely limited to ceremonial and symbolic tasks.

Women who engaged in prostitution or other forms of “immorality” could be punished with fines, beatings, or even death, while men who committed similar offenses often received lighter penalties.

Overall, the legal rights and status of women in Ancient Egypt varied depending on their social class and marital status, but they generally had limited agency and power within society.

Bullet points summarizing key points:

- Women could be married at 12 or 14; men typically reached marriageable age at 15.

- Marriage was often arranged by families for economic or social gain.

- Women had limited control over their own lives and choices within the household.

- Some women owned property and participated in business dealings, although this may have been more common among wealthy and educated women.

- Female officials held important roles in government, but their responsibilities were largely limited to ceremonial and symbolic tasks.

References:

- “The Instruction of Ptahhotep.”

- Horemheb’s Law Code (around 1323 BCE).

- “Edict of Horemheb.”

In ancient Egypt, women enjoyed relatively high social status and legal rights compared to other civilizations of the time. This was largely due to the country’s long history of matriarchal societies and the influence of goddess worship.

The concept of “ma’at” or truth, justice, and balance played a central role in ancient Egyptian society, which helped to establish women’s rights as an integral part of the social fabric. The idea of ma’at was personified by the goddess Ma’at, who embodied these principles.

Women in ancient Egypt were considered capable of owning property, participating in trade, and engaging in various economic activities. They could also work as weavers, bakers, or in other occupations, and even own their own businesses.

The Egyptian marriage system was based on a form of partnership between the husband and wife, known as “sedjer.” In this arrangement, both partners shared equal rights to the property they acquired during the marriage. If the marriage ended through divorce or death, the woman had the right to keep her dowry and any other possessions she had accumulated.

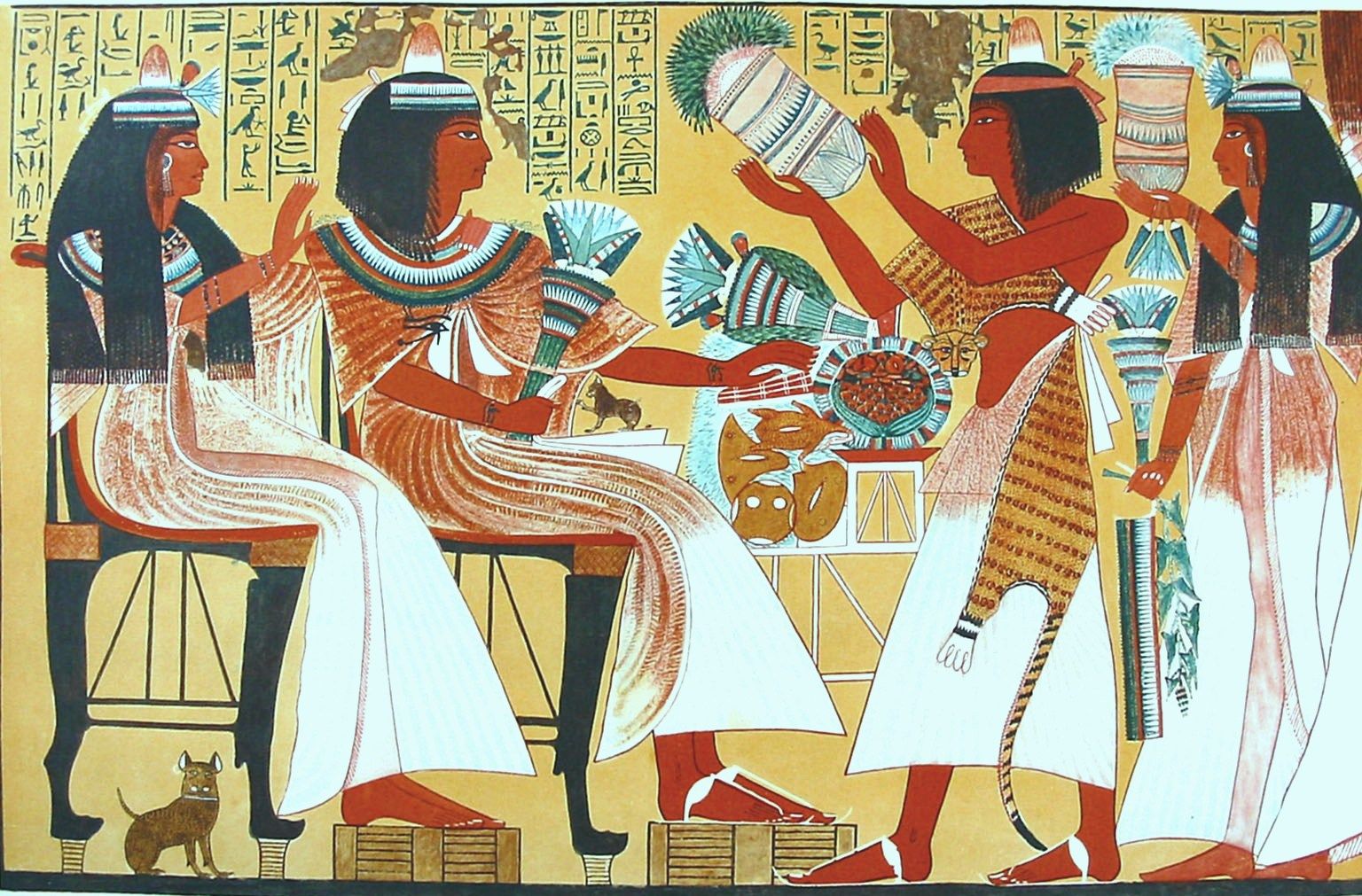

Women also played an important role in ancient Egyptian society through their participation in family life and social institutions. They were responsible for managing the household and bringing up children, as well as participating in communal activities such as festivals and processions.

Although women’s rights in ancient Egypt were generally more advanced than those found in other civilizations of the time, there are still records of patriarchal practices and restrictions on female participation in certain areas of society. For example, women were excluded from holding high-ranking government positions or participating in military activities.

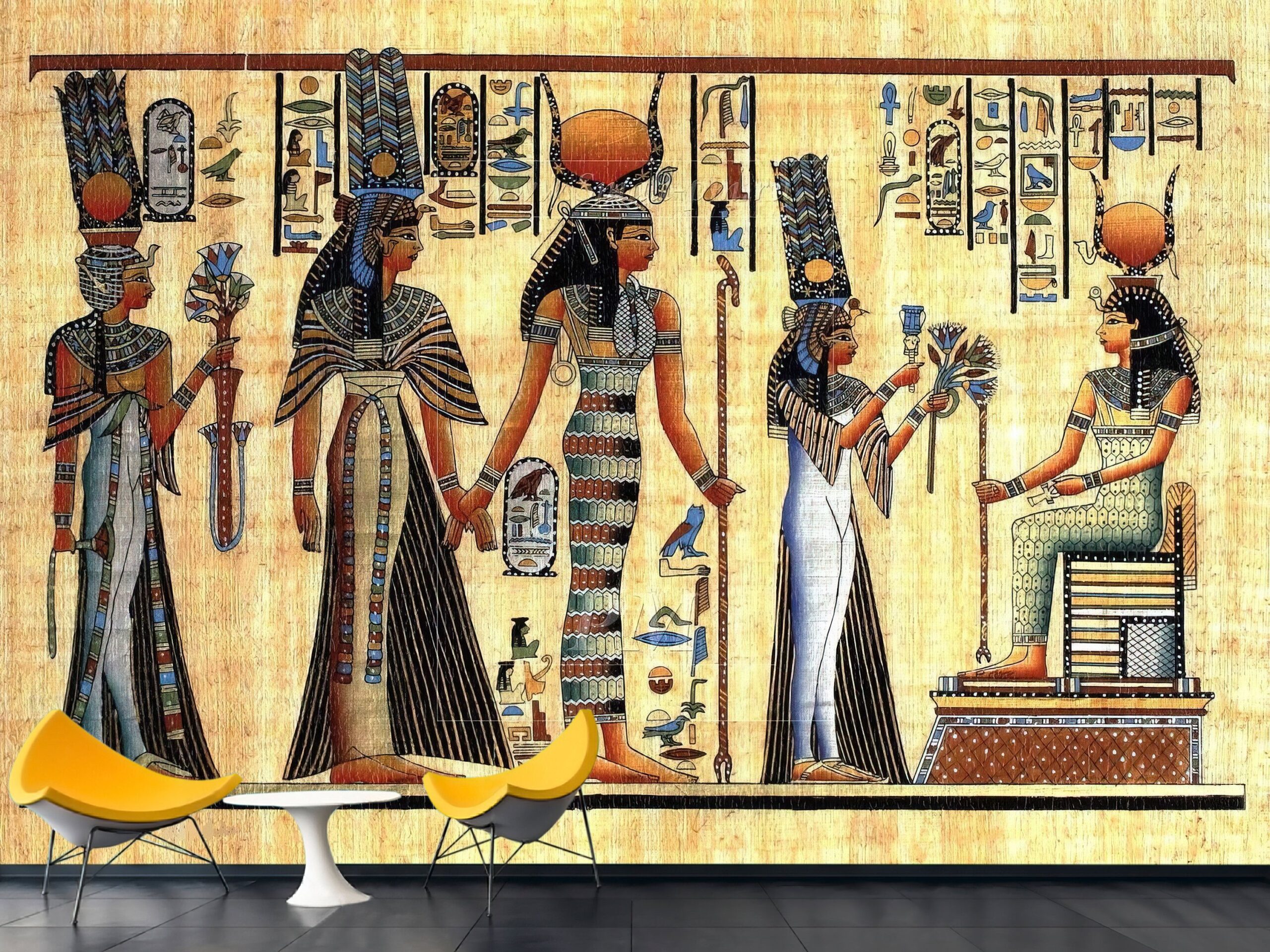

The worship of goddesses such as Isis, Hathor, and Neith was also influential in shaping women’s rights in ancient Egypt. These deities symbolized feminine power and fertility, which helped to promote a culture of reverence for women and their roles within society.

The ancient Egyptian civilization is renowned for its advanced societal structure, with a well-defined system of laws and regulations governing various aspects of life. A crucial aspect of their social hierarchy was the status accorded to women within this society, which varied significantly from that prevalent in other civilizations of the time.

According to historical records and archaeological findings, women in ancient Egypt enjoyed relatively more rights than their counterparts in many other cultures of the era. One of the key aspects of women’s legal rights was property ownership. Women had the right to own and inherit property, which included land, houses, and even slaves.

However, this right was not absolute. In cases where a woman was married, her property often became subject to her husband’s control or management under certain circumstances, such as if he needed funds for their family’s well-being. Despite these restrictions, women continued to have legal rights over their own personal belongings.

Another significant aspect of women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt was the right to participate in various aspects of society, including legal and religious proceedings. Women could act as witnesses in court, sign legal documents, and even serve as priestesses in temples dedicated to certain deities. This level of participation was rare for women in other ancient civilizations.

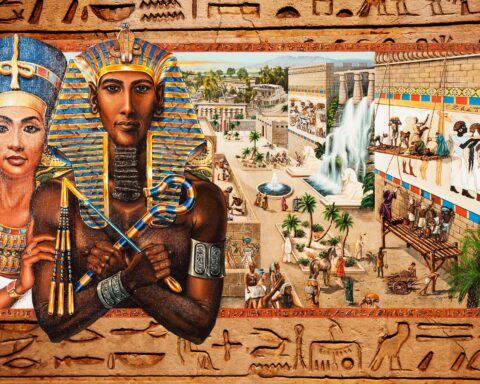

One notable case is that of Hatshepsut, who rose to become one of the most successful pharaohs of Egypt, ruling alongside her stepson Thutmose III and later taking on full power following his death. Her success demonstrates the potential for women in positions of power within Egyptian society, though it was a rare occurrence.

Marriage laws also provided some level of protection for women. A woman had the right to divorce her husband without penalty if he committed certain acts against her, such as adultery or failure to provide for her needs. Additionally, a divorced woman retained her property rights and could even choose not to marry again, although she risked losing any future inheritance from her family.

Finally, ancient Egyptian society made provision for women’s education and employment opportunities. While the majority of women did engage in domestic activities, there were records of women who worked as scribes, which would have required a significant level of literacy and education. This indicates that while societal roles for women might have been limited, they were not entirely excluded from areas considered intellectual or professional.

In summary, despite certain restrictions and limitations, women in ancient Egypt enjoyed rights and privileges under the law that surpassed those found in many other societies of the time. Property ownership, legal participation, marriage laws, education, and employment opportunities all contributed to a unique social hierarchy where women were not entirely marginalized from societal affairs.

Marriages were often arranged by family members.

In ancient Egypt, marriage was often seen as a means to secure alliances between families rather than a union based on romantic love.

The process of selecting a spouse could be quite involved, with parents and other family members playing a significant role in the decision-making process.

While there is no clear evidence of a formal “arranged marriage” system, it’s widely believed that many marriages were indeed arranged by family members to secure advantageous alliances, inheritances, or social status.

Women’s Legal Rights in Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians had a relatively advanced understanding of women’s rights and legal protections, especially when compared to other ancient civilizations.

One notable example is the “Edict of Horemheb,” which granted women significant property rights and the ability to manage their own businesses.

In addition, women in ancient Egypt were allowed to engage in various professions, including medicine, writing, and even priesthood.

The Role of Women in Ancient Egyptian Society

Women played a vital role in ancient Egyptian society, often holding positions of power and influence within the family and community.

- Some women served as priestesses or held high-ranking administrative positions.

- Others were skilled craftsmen, artists, or writers, while many managed households and supervised domestic staff.

Marriage Laws and Contracts

Marriage laws in ancient Egypt emphasized the concept of “conjugal property,” where both spouses shared ownership of assets acquired during marriage.

- Wives were entitled to a portion of their husband’s inheritance, as well as any assets they brought into the marriage.

- Husbands, on the other hand, were responsible for providing support and maintenance to their wives and children.

The Marriage Contract was an important legal document that outlined the terms and conditions of the union.

- It included provisions for property ownership, inheritance, and child custody.

- The contract could also specify any restrictions or limitations on the wife’s rights, such as her ability to manage property or engage in business activities.

Divorce Laws

Divorce laws in ancient Egypt allowed for relatively easy dissolution of marriage, often at the behest of either spouse.

- Husbands could initiate divorce by presenting a petition to the court.

- Wives also had the right to seek divorce, particularly if they were abandoned or mistreated by their husbands.

Conclusion

- In conclusion, ancient Egyptian women enjoyed relatively high levels of legal protection and social status, especially when compared to other ancient civilizations.

- Their rights and freedoms were recognized through various laws, contracts, and customs, including the Marriage Contract and Divorce Laws.

- These provisions reflect a more egalitarian approach to marriage and family law in ancient Egypt, where women played a significant role in society and enjoyed a degree of autonomy and agency.

The woman’s consent was not always required.

The ancient Egyptian society was known for its complex system of laws and social norms, which governed the lives of both men and women. However, when it came to matters of consent in marriage and relationships, the concept of consent was not as straightforward or absolute as it is today.

In ancient Egypt, marriage was often a matter of family arrangement and social status rather than love or personal choice. The process of obtaining a wife for a man often involved his parents or other relatives selecting a suitable bride, who was usually much younger than her husband-to-be.

The woman herself had little to no say in the matter and was expected to accept the marriage proposal without question. This was partly due to the societal norms that emphasized obedience and submissiveness in women. The notion of a woman having the right to refuse or consent to a marriage proposal would have been seen as unusual and even scandalous.

Furthermore, ancient Egyptian law did not recognize the concept of marital rape or consent within marriage. Women were often expected to be available to their husbands for sexual purposes, and resistance was not seen as an option. The idea that a wife might refuse her husband’s advances would have been considered grounds for divorce or even punishment.

However, it is worth noting that some exceptions existed in ancient Egyptian society. For example, women from the lower classes who were able to earn their own living through trade or other means often enjoyed greater autonomy and freedom than their wealthier counterparts. Additionally, some female deities such as Isis and Nephthys were revered for their independence and strength.

Despite these exceptions, it is clear that in ancient Egypt, the woman’s consent was not always required or respected. Women’s rights were severely limited, and they were often treated as property rather than individuals with agency and autonomy.

The lack of recognition of women’s consent in ancient Egyptian society highlights the importance of ongoing struggles for gender equality and human rights. It also serves as a reminder that the notion of consent is a relatively modern concept that has evolved over time, influenced by changing social norms and values.

Maintenance and property rights were specified in marriage contracts.

In ancient Egyptian society, marriage contracts played a crucial role in defining the rights and responsibilities of both partners within the relationship.

While modern conceptions of equality and individual rights did not exist at that time, these contracts did contain provisions related to maintenance and property rights, albeit often favoring male dominance.

The marriage contract typically specified the terms under which a woman was entitled to financial support or maintenance from her husband in case he passed away or abandoned her. This might include provisions for food, clothing, shelter, and other necessities of life.

However, these rights were often contingent upon the woman’s behavior and loyalty to her husband, with potential penalties for infidelity or other forms of disloyalty. In some instances, a woman could be forced to return her dowry (a payment made by her family at the time of marriage) if she failed to meet these expectations.

As for property rights, women in ancient Egypt were not necessarily considered full owners of property they brought into the marriage. In many cases, their dowries might be managed jointly with their husbands or even used as a source of leverage over them.

The situation was slightly more favorable for women from wealthier backgrounds who could negotiate more favorable terms within their contracts. Some women even retained control over certain assets and properties throughout their lives, although these cases were relatively rare.

It’s worth noting that the rights granted to women through marriage contracts varied across different social classes and geographic locations within ancient Egypt. Those from higher-ranking families or living in urban centers might have enjoyed greater protection and more comprehensive provisions compared to those from lower social strata or rural areas.

Ultimately, while these contracts did contain elements related to maintenance and property rights, they were often shaped by patriarchal norms that reinforced male dominance within the family unit. The rights granted to women remained limited, reflecting the broader societal attitudes toward their roles and status at that time.

The concept of women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt has been a subject of interest for scholars for centuries. The ancient Egyptians, who lived around 3100 to 332 BCE, had a relatively advanced society with a well-developed system of laws and governance. While it may seem counterintuitive, the ancient Egyptian legal system provided significant protection and privileges for women compared to other ancient civilizations.

One of the key aspects of women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt was their right to own property and participate in the economy. Women were allowed to inherit and purchase property, including land, houses, and personal items. In fact, it was not uncommon for women to be among the wealthiest individuals in society due to their control over family estates and business interests.

Women also had the right to enter into contracts and engage in trade on their own behalf. They could lease land, hire laborers, and participate in commercial transactions without needing the approval of a male guardian or husband. This level of autonomy was unusual for ancient times, where women’s roles were often limited to domestic duties.

Marriage laws in ancient Egypt also offered some protection to women. While marriage was often arranged by families, the couple had significant rights and obligations towards each other. Wives had the right to demand financial support from their husbands if they failed to provide for them, and husbands were obligated to maintain a standard of living that allowed their wives to live comfortably.

Divorce laws also favored women in some respects. While divorce was generally difficult to obtain, wives could initiate divorce proceedings if their husbands had abandoned or mistreated them. Women were also entitled to retain ownership of property acquired during marriage and could negotiate custody arrangements for any children.

Despite these advances, it’s essential to note that social and economic status often influenced the application of women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt. Wealthy and high-ranking women generally enjoyed greater privileges and protections than those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

Furthermore, women who were part of the royal family or held positions of power had even more extensive rights and influence than their peers. For example, Hatshepsut, one of the most famous female pharaohs in Egyptian history, exercised significant authority during her reign (1479-1458 BCE).

It’s also worth noting that while women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt were more developed than those of many other societies at the time, they still existed within a patriarchal framework. Women were often seen as secondary to men and subject to certain restrictions and expectations.

In conclusion, the legal system of ancient Egypt provided significant protection and privileges for women, including property ownership, contractual autonomy, and rights within marriage. While social and economic status played a role in determining these rights, they represented an important step forward for women’s empowerment in ancient times.

Women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt were influenced by the country’s complex social hierarchy, which was divided into different classes based on their occupation, wealth, and social status.

The female population was also categorized based on their marital status, with married women holding a relatively higher position than unmarried women. Married women enjoyed certain benefits such as owning property and participating in economic activities, but they were still largely under the control of their husbands and male relatives.

Women’s rights to inheritance were determined by the legal code known as the “Code of Hammurabi” which was not applicable in ancient Egypt. However, the Egyptian law stated that women had a right to inherit property from their parents and relatives.

The concept of “patronage,” where a woman would work for a patron who provided her with food and shelter in exchange for labor or services, played a significant role in the lives of many Egyptian women. This system allowed women to maintain some autonomy and independence from male relatives, but it also created power imbalances between patrons and their female employees.

One notable exception to the general restrictions on women’s rights was found in ancient Egypt during the reign of Pharaoh Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE). During her time as pharaoh, Hatshepsut implemented policies that granted women greater autonomy and freedom. She allowed women to participate in trade and commerce, hold public office, and even serve in the military.

Despite these advancements, it is essential to note that women’s rights were still limited by societal expectations and patriarchal norms. Women who defied convention or challenged male authority risked punishment and social ostracism. Nevertheless, the relatively high status of some women in ancient Egyptian society suggests a level of acceptance and respect for female agency.

The study of women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt highlights the importance of understanding the cultural context in which they lived. By examining these historical norms, we can gain insights into the complex and multifaceted nature of gender relations throughout history.

Economic Rights

Property Ownership and Inheritance

- In Ancient Egypt, property ownership and inheritance laws were governed by a complex system that varied depending on social class, gender, and family relationships.

- Women’s legal rights to property and inheritance in Ancient Egypt are well-documented through various sources such as papyri, tomb inscriptions, and literary texts.

- Under Ancient Egyptian law, women could own and inherit property, but their rights were often limited compared to those of men.

- The most significant legislation affecting women’s property rights was the Edict of Horemheb, which granted women equal inheritance rights with their husbands’ relatives in cases where the couple did not have children.

- The Edict of Horemheb is considered a landmark law that protected the property rights and interests of women in Ancient Egypt. However, its application and implementation varied depending on social context and regional jurisdictions.

Women’s ownership of property in Ancient Egypt often came through various means such as:

- marriage, where a woman would bring her dowry or receive gifts from her husband.

- inheritance, where a woman would inherit property from her relatives, particularly her parents or siblings.

- purchase, where a woman could buy property using her own means, such as selling goods or receiving loans.

- Property ownership by women was often subject to restrictions and limitations, including:

- Usufruct, which allowed the owner of the property to use and enjoy it without transferring legal title.

- guardianship, where a male relative or the state would oversee the management and disposal of a woman’s property in cases where she was deemed incapable or inexperienced.

Despite these limitations, women in Ancient Egypt could participate in economic activities such as trade, commerce, and industry. Some notable examples include:

Mereret, who owned a significant amount of land and property in the 15th century BCE.

Nefertiti, who managed her own estate, including real estate and goods, during her marriage to Pharaoh Akhenaten.

Overall, women’s legal rights to property and inheritance in Ancient Egypt were shaped by a complex interplay of social class, family relationships, and legislation. While their rights were often limited compared to those of men, there are examples of women who exercised significant control over their property and estates.

Women could own and inherit property, including land and businesses.

In ancient Egypt, women enjoyed a relatively high degree of independence and legal rights compared to other societies of the time. One significant aspect of their rights was the ability to own and inherit property, including land and businesses.

The law codes of ancient Egypt, such as the Code of Hammurabi and the Edict of Hapi, demonstrate that women were recognized as individuals with their own property and financial interests. For example, a woman could purchase, sell, or gift property without the need for her husband’s consent or approval.

Women’s ability to inherit property was also well-established in ancient Egyptian law. In many cases, daughters inherited equal shares of property alongside their brothers, including land, livestock, and other assets. This was a significant departure from many other societies, where daughters typically received smaller portions of the family estate or were denied inheritance altogether.

In addition to owning and inheriting property, women in ancient Egypt also had the right to engage in business and economic activities. Women could work as merchants, traders, or artisans, and own their own businesses or participate in joint ventures with others. Some women even became prominent entrepreneurs, accumulating wealth and influence through their commercial endeavors.

The fact that women could own and inherit property, including land and businesses, reflects the relative social and economic equality between men and women in ancient Egypt. While there were certainly limitations on women’s roles and opportunities in this society, their legal rights and economic freedoms were more extensive than those enjoyed by women in many other cultures of the time.

It is worth noting that these rights were not uniformly applied across all social classes or regions in ancient Egypt. Women from wealthy or influential families often had greater access to education, property, and economic opportunities than those from lower socio-economic backgrounds. Additionally, women’s rights may have varied depending on the specific laws and customs of different cities or districts within Egypt.

Despite these limitations, however, the existence of strong legal protections for women’s property and economic interests in ancient Egypt is a significant testament to the relative social and economic equality of this society. It highlights the importance of recognizing the agency and autonomy of women as individuals with their own financial interests and aspirations.

The legacy of ancient Egyptian law can be seen in later societies that drew on these principles, such as medieval European kingdoms and modern democratic states. The recognition of women’s property rights and economic freedoms has been an ongoing theme throughout human history, reflecting the gradual evolution of social and economic norms towards greater equality and justice.

The women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt are a subject of significant interest among historians and scholars, particularly due to the relatively progressive nature of their social and legal framework compared to other ancient civilizations. Ancient Egyptian society was known for its strict division between men and women, with men typically holding positions of power and authority.

However, despite this patriarchal bias, women in ancient Egypt enjoyed a higher degree of freedom and rights than their counterparts in many other parts of the world at that time. Some key aspects of women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt include:

- The right to own property: Women had the right to inherit, buy, sell, and own property in their own name, including land and houses.

- The right to participate in trade and commerce: Women were allowed to engage in various professions such as weaving, pottery-making, and trading, which gave them a degree of economic independence.

- The right to enter into contracts: Women could sign contracts, including marriage contracts, and had the ability to negotiate terms with men.

One notable example of women’s rights in ancient Egypt is the case of Merneith, a queen who ruled as regent for her stepson and was likely one of the first female pharaohs in Egyptian history. Her existence demonstrates that women could hold significant power and influence within society, even if it was rare.

Despite these advances, there were also limitations to women’s rights in ancient Egypt, including:

- Property rights: While women had the right to own property, they often needed their husband or other male relatives to manage and administer it for them.

- Punishment for adultery: Women who were found guilty of adultery could face harsh punishment, including being burned at the stake or having their eyes gouged out.

The status of women in ancient Egypt also varied depending on their social class. For example:

- Wealthy women: Women from wealthy families often enjoyed a high degree of freedom and independence, with access to education and economic opportunities.

- Working-class women: Women from poorer backgrounds often had limited access to education and employment opportunities, and were more likely to be involved in domestic work or other low-skilled industries.

In summary, while women’s rights in ancient Egypt were not without their limitations, they represented a significant improvement over the social norms of many other cultures at that time. The fact that women could own property, participate in trade and commerce, and enter into contracts demonstrates a high degree of respect for women’s autonomy and agency.

Women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt were surprisingly progressive for their time, with many laws granting women significant autonomy and property ownership.

The Edict of Hatusil III (1258-1236 BCE) prohibited the sale or enslavement of any woman who had not given her consent to marriage, while also ensuring that she retained her right to inheritance and dowry.

Ancient Egyptian law codes such as the Middle Kingdom’s “Instructions of Onchsheshonqy” and the New Kingdom’s “Westcar Papyrus”, emphasize the importance of a woman’s testimony in court proceedings. This recognition of a woman’s agency in legal matters underscores their status as equal citizens under the law.

Women could also own, buy, and sell property independently, with many female pharaohs like Hatshepsut and Nefertiti accumulating significant wealth through land ownership and trade. This freedom to engage in economic activities was a hallmark of women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt.

Ancient Egyptian women enjoyed greater social mobility than their counterparts in other civilizations, with many rising to high-ranking positions within the royal court and bureaucracy. The fact that many female officials held key administrative roles highlights their ability to hold power and influence within society.

Divorce laws also favored women’s rights, allowing them to initiate divorce proceedings if their husbands failed to provide for them or commit adultery. In addition, women could retain custody of their children in the event of a divorce, giving them significant control over family dynamics.

The importance of protecting women from exploitation and abuse was reflected in ancient Egyptian law, with punishments prescribed for men who committed acts of violence against women. For example, if a man was found guilty of beating his wife, he could face severe penalties, including imprisonment or even death.

Despite these advances, women’s rights were not without their limitations. They remained largely excluded from the priesthood and were restricted from participating in public offices, except for those that involved managing royal property or estates.

However, overall, ancient Egyptian society offered a unique environment where women enjoyed considerable legal freedom and autonomy compared to other civilizations of its time. This enduring legacy can be seen as a testament to the progressive nature of ancient Egypt’s laws and social institutions.

Wives had the right to use and dispose of their husbands’ property.

In ancient Egyptian society, women’s legal rights varied depending on their social class and marital status. While wives did not have outright ownership of their husband’s property, they were granted specific privileges regarding its use and disposal.

Under the Code of Hammurabi, which was in effect during the 18th dynasty (circa 1550-1292 BCE), a wife had the right to use her husband’s property for her personal needs. This included using the household furnishings, clothing, and jewelry for her own benefit.

Additionally, if a husband were to die without a will, his widow was entitled to one-third of his estate. The remaining two-thirds would be distributed among his children or other relatives, as per the ancient Egyptian law known as “the right of the deceased’s heir.”

The wife also had the authority to administer her husband’s property during his absence. For example, if a man were to go on military campaign, his wife could manage and oversee the household and its assets until he returned.

It’s worth noting that these rights applied primarily to wives of high-ranking officials or members of the royal family. Women from lower social classes had fewer legal protections and were often at risk of exploitation by their husbands or other men in power.

The concept of joint ownership, however, was not commonly practiced among ancient Egyptians. Husbands typically held sole title to property, while their wives managed it on behalf of the household.

Despite these limitations, ancient Egyptian women’s rights regarding property were relatively advanced compared to many other cultures of the time. The privileges granted to them reflect a recognition that women played a significant role in managing households and overseeing family assets.

The significance of women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt cannot be overstated. They demonstrate an early example of attempts to establish equality between men and women, particularly within marriage. These provisions underscored the importance of recognizing women as active participants in social, economic, and political spheres of their time.

Daughters had a share in family wealth upon father’s death.

In ancient Egyptian society, the concept of inheritance and property rights was relatively advanced compared to other cultures at that time.

The majority of the population was rural and relied on agriculture for their livelihood. Farming communities often owned small plots of land and other productive assets such as livestock or tools.

Upon a father’s death, daughters had a share in family wealth, which included the inheritance of property, goods, and even some rights to participate in familial business ventures.

The social structure of ancient Egyptian society was patriarchal. This means that men held most positions of power and authority, but it also meant that there were opportunities for women to own property and exercise economic agency within certain limitations.

Daughters often inherited the right to own land or other productive assets if their father died without a will, or in cases where he did not have a son. In such instances, daughters might inherit one-fifth to one-third of their father’s property upon his death.

The Code of Hammurabi from ancient Babylon, which is considered one of the earliest surviving sets of written laws, states that a woman who married her younger sister to her brother-in-law after she became widowed would have 1/2 of her deceased husband’s goods if there were no children. This highlights how women could manage assets in cases where there were no direct male heirs.

Marriage in ancient Egypt was also influenced by family and social status, particularly among the elite classes. Marriages often involved complex webs of alliances between families to maintain or increase their power and wealth. Women’s ability to inherit property and participate in these marriages meant they could gain access to resources and networks beyond those of other women.

It is essential to consider the role of class when looking at ancient Egyptian society. The wealthy and powerful were more likely to have a share of family wealth upon their father’s death due to owning greater amounts of land, goods, or participating in large-scale business ventures. This created a self-reinforcing system where those who already held power were even more likely to inherit it.

The practice of women inheriting property and rights within ancient Egyptian society has been observed by historians through archaeological discoveries, written records like the Code of Hammurabi, and social and economic contexts.

The women of ancient Egypt enjoyed relatively more rights compared to their counterparts in other parts of the world. The code of laws, known as the Edict of Haremhab (also known as the Harris Papyrus), which was written during the reign of Pharaoh Haremhab in the 13th century BC, granted women some basic rights and privileges.

One significant aspect of women’s rights in ancient Egypt was the right to inherit property. Women were allowed to own land and other forms of property, which could be passed down through generations. This was a considerable departure from other cultures where women had limited or no rights to inheritance.

Women also enjoyed a certain degree of freedom in terms of marriage and divorce. They were not forced into marriages that they did not consent to, and they had the right to initiate divorces if their husbands were guilty of serious transgressions such as impotence or adultery.

Another significant aspect of women’s rights in ancient Egypt was their access to education. Women from wealthy families could receive an education, which included learning to read and write. This gave them a certain level of independence and allowed them to participate in the social and economic activities of society.

Women also had some degree of participation in politics and governance. They were eligible to serve as priestesses in the temple, which gave them a level of influence and authority within the community. Some women even rose to positions of power and became important advisors to the pharaohs.

In addition to these formal rights, women in ancient Egypt also enjoyed a degree of social status. They were considered to be equal companions of their husbands and were expected to participate in all aspects of family life. This included managing household affairs, educating children, and contributing to economic activities such as spinning and weaving.

It is worth noting that while women in ancient Egypt enjoyed some significant rights, they still faced many challenges and inequalities. They were often subject to patriarchal attitudes and biases, which limited their opportunities for social mobility and participation in public life. Additionally, the fact that women’s roles were largely confined to domestic and familial spheres meant that they had little opportunity to pursue careers or participate in the broader economy.

The ancient civilization of Egypt is renowned for its advanced societal structures, including laws that governed the roles and rights of women. Despite the common misconception that ancient Egyptian society was patriarchal and oppressive towards women, archaeological evidence and literary records suggest that women enjoyed a relatively high degree of social status and legal protection.

In terms of property rights, women in ancient Egypt had the ability to own and inherit property, including land, houses, and other assets. This is evident from the discovery of tomb inscriptions and wills that detail the distribution of wealth among family members, often with women playing a significant role in the transmission of property.

The famous “Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor” from the Old Kingdom era features a female character named Nefetari, who is described as a wealthy merchant capable of navigating international trade and commerce. This narrative highlights the economic agency and entrepreneurial spirit that women like Nefetari embodied in ancient Egyptian society.

Laws governing marriage also demonstrated a degree of equality between men and women. For instance, the “Edict of Horemheb” from the 18th dynasty mandated that husbands provide their wives with maintenance and support during divorce or separation. This legislation suggests that the state recognized a woman’s right to economic security and support within the family unit.

Regarding personal rights and freedoms, women in ancient Egypt enjoyed greater autonomy than previously acknowledged. Tomb inscriptions and literary records reveal cases of women engaging in various professions, including priestesses, healers, and scribes. These examples challenge the notion that women were confined to domestic roles, demonstrating instead a diversity of occupations and spheres of influence.

Feminist scholars have long argued that ancient Egyptian society was more progressive towards women than often credited. The discovery of artifacts such as the “Women’s Temple at Deir el-Medina” provides evidence of a female-dominated spiritual community that exercised significant influence within the temple complex. This find supports the idea that women held considerable social and religious authority in ancient Egypt.

However, it is essential to acknowledge the limitations and complexities inherent in interpreting historical evidence. While ancient Egyptian society appears to have been relatively progressive towards women’s rights, it is also clear that patriarchal structures persisted and influenced societal norms. The interplay between these opposing forces has sparked ongoing debates among historians and scholars, who continue to refine our understanding of women’s lives in ancient Egypt.

Laws Governing Women’s Actions

Criminal Liability and Punishment

The concept of Criminal Liability and punishment during ancient times was shaped by the societal norms, laws, and cultural values of the time. In Ancient Egypt, criminal liability was a complex issue that varied depending on factors such as the nature of the crime, social class, and gender.

The Egyptian Law Code (circa 1900 BCE), also known as the Edict of Horemheb, outlined punishments for various crimes. However, it did not explicitly address women’s rights or their criminal liability. Nevertheless, through a close examination of court records and literary works from that era, historians have pieced together information on the treatment of women in ancient Egypt.

Punishment for Women: In general, punishments for women were often more severe than those meted out to men. This was partly due to societal attitudes towards women’s roles and their perceived status within society. Women who committed crimes such as adultery or theft might face fines, forced labor, or even death.

Criminal Liability of Women: While the concept of civil responsibility for one’s actions was present in ancient Egypt, women were often exempt from it. In cases where a woman committed a crime, her male guardian might be held responsible instead. This reflects a broader societal tendency to treat women as minors who required supervision and protection.

Women’s Legal Rights: Women in Ancient Egypt did have some legal rights, although these were limited compared to men. For instance, married women retained control over certain property rights and could make legal agreements without the approval of their husbands. However, these rights were often conditional upon meeting specific requirements.

Social Context: The social context in which women lived in ancient Egypt significantly influenced their experiences with civil liability. Women from higher social classes may have had greater autonomy and protection under the law compared to those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Additionally, regional variations in laws and customs also affected how women’s legal rights were perceived.

Sources of Information: Most information about ancient Egyptian laws comes from literary sources such as The Edict of Horemheb, which provides valuable insight into the societal norms surrounding punishment and crime. Archaeological findings, including tomb inscriptions and court records, also contribute significantly to our understanding of these topics.

Key Points:

- Criminal liability in ancient Egypt was influenced by societal attitudes towards women’s roles and status within society.

- Punishments for women were often more severe than those meted out to men.

- The Egyptian Law Code (Edict of Horemheb) did not explicitly address women’s rights or their criminal liability.

- Women from higher social classes may have had greater autonomy and protection under the law compared to those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

Women were subject to different penalties for the same crimes as men.

The ancient Egyptian legal system had a complex and often contradictory approach to women’s rights, with various laws and regulations governing their status and treatment.

One area where women were subject to different penalties for the same crimes as men was in matters of marriage and family law.

In cases of adultery, for example, a married woman who committed adultery could be punished by having her nose cut off or being forced to divorce her husband.

A man convicted of adultery, on the other hand, might face a lighter penalty, such as a fine or a temporary suspension from public office.

Women were also subject to harsher penalties for crimes related to property and wealth, with laws governing inheritance and dowries often favoring men over women.

In some cases, a woman who was accused of stealing or embezzlement might be forced to confess to the crime and then punished accordingly, whereas a man convicted of the same offense might receive a lighter sentence or even go unpunished.

This disparate treatment of women in ancient Egyptian law reflects a broader societal attitude that viewed women as inferior to men and denied them many of the rights and privileges enjoyed by their male counterparts.

However, it’s also worth noting that some female pharaohs, such as Hatshepsut and Nefertiti, managed to circumvent these laws and wield significant power in ancient Egyptian society, highlighting the complexities and contradictions of women’s roles within the culture.

In ancient Egypt, women’s legal rights were relatively progressive compared to other civilizations of the time. Although women did not have the same status as men in society, they enjoyed a degree of independence and freedom that was unusual for women during this period.

The earliest evidence of women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt comes from the Old Kingdom (2613-2181 BCE), where women were considered to be property owners. They could inherit land and property, and even conduct business transactions independently. In fact, some female property owners were even allowed to participate in temple rituals.

During the Middle Kingdom (2040-1750 BCE), women’s rights continued to expand. They were granted greater autonomy in marriage and divorce, with the ability to initiate divorce proceedings themselves. This marked a significant shift from the previous practice, where men had complete control over marriage and property.

The law code of the pharaoh Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) specifically recognized women’s rights to own property, conduct business, and participate in temple rituals. Her laws even granted women the right to engage in trade and commerce on an equal basis with men.

In ancient Egyptian society, a woman’s status was often tied to her family and social position. Women from higher-ranking families had more opportunities for education and personal development than those from lower-class backgrounds. However, this did not necessarily mean that they were more restricted in their personal choices or freedoms.

One of the most significant aspects of women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt was the concept of “ma’at.” Ma’at referred to the balance of justice and morality in society, which emphasized the importance of respecting and honoring the principles of truth, honesty, and compassion. This concept encouraged both men and women to maintain a high level of integrity and moral responsibility.

Unfortunately, despite these progressive laws and social norms, ancient Egyptian women still faced significant challenges and restrictions. They were often forced into marriage at a young age, and their rights were frequently ignored or subverted by the patriarchal society in which they lived. Nevertheless, the evidence suggests that women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt were more extensive than those found in many other civilizations of the time.

Women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt were relatively advanced compared to other civilizations at the time. However, women’s roles and opportunities varied depending on their social class and status.

The Code of Hammurabi, which was adopted by the Egyptians during the New Kingdom period (1530-1070 BCE), gave women some rights and protection under law, including:

- The right to own property and receive inheritances

- Protection from domestic violence and abuse

- The right to participate in family and business decisions

The female pharaohs of ancient Egypt, such as Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) and Cleopatra (51 BCE-30 BCE), held significant power and influence, often ruling in their own right. They were responsible for making key decisions on matters of state, diplomacy, and war.

In addition to these high-profile examples, many other women from various social classes held important positions and played vital roles in ancient Egyptian society. Women served as:

- Administrators and bureaucrats

- Priestesses and spiritual leaders

- Artists and artisans

- Business owners and entrepreneurs

Despite these advances, women’s rights in ancient Egypt were not without limitations. Women’s roles were often defined by their relationships with men, such as marriage, family, or social status.

The ideal woman was expected to be subordinate to her husband, father, or other male relatives. Women who deviated from this norm, such as those who sought education or economic independence, faced societal disapproval and potential legal consequences.

Women faced harsher punishments, such as mutilation or imprisonment.

- In ancient Egyptian society, women’s legal rights were limited and often subject to harsher punishments compared to men.

- The ancient Egyptian code of law, known as the Edict of Hattusilis, demonstrated a clear bias towards males in terms of punishment and privileges.

- Women who committed adultery or engaged in extramarital relationships were punished with various forms of mutilation, such as branding on the forehead or the cutting off of their nose.

- Moreover, women’s testimony in court was often given little weight, and they were frequently subjected to imprisonment for minor offenses.

- In cases of theft, a woman could be imprisoned for up to 30 days, while her male counterpart might receive only a few hours of public flogging as punishment.

- The harsher punishments faced by women were reflective of the patriarchal nature of ancient Egyptian society, where men held significant power and control over their families and communities.

- Women who did not conform to societal expectations or norms often found themselves facing severe consequences for their actions.

- In one recorded instance, a woman who was accused of incest with her brother was sentenced to death by hanging.

- This demonstrates that women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt were far from equal to those of men and that they were frequently subjected to harsher punishments for even minor transgressions.

- The lack of protection for women under the law contributed to a broader culture of patriarchy and gender inequality, where women were often treated as second-class citizens.

No distinction was made between women of high or low social status in sentencing.

The legal system of Ancient Egypt, as evidenced by the Ptolemaic and Roman period papyri, suggests that there was no significant distinction made between women of high or low social status when it came to sentencing. This is contrary to what one might expect in a society with such pronounced social hierarchies.

Despite the existence of different classes within Egyptian society, including nobles, priests, and commoners, as well as free and slave populations, the legal code appears to have treated women across these categories relatively similarly. This is evident in the types of crimes that were punished, as well as the severity of those punishments.

Some examples of this can be seen in the following cases:

- In one papyrus, a slave woman who had committed adultery was sentenced to be stoned. This punishment would have been the same for a free woman who committed the same crime.

- Another example is that of a high-ranking noblewoman who was accused of theft and found guilty. She was punished with confiscation of her property, which was a common penalty for those convicted of this crime across all social classes.

The lack of distinction between women’s legal rights in Ancient Egypt is also reflected in the fact that the same laws applied to married women as to unmarried ones. This means that married women did not have greater or lesser protection from abuse, divorce, and other legal issues compared to their unmarried counterparts.

In addition, the papyri suggest that the law treated women equally with respect to property rights. Married women were allowed to manage and own their own property, including real estate and movable goods. This was a significant departure from many other ancient civilizations, where married women typically had very limited control over their assets.

Finally, it’s worth noting that while the Egyptian legal system did not make distinctions between high- and low-status women in sentencing, this does not necessarily mean that they were treated equally in all aspects of society. Social hierarchies often influenced an individual’s access to education, economic opportunities, and social mobility.

Despite these limitations, the Egyptian legal system was notable for its relative egalitarianism when it came to the rights of women across different social classes. This is evident in the fact that women were treated similarly under the law, regardless of their status as nobles, slaves, or free individuals.

The women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt were influenced by the society’s patriarchal nature. The pharaohs held absolute power, with authority extending to laws governing women’s roles and status in society.

The Egyptian legal code, known as Ma’at, emphasized justice and social order. In practice, however, this often meant that women’s rights were limited, particularly with regard to marriage, property, and personal autonomy.

Women could own property, but only if their husbands or other male relatives managed it on their behalf. This was due in part to the concept of “ma’at,” which held that a woman’s value lay not in her own identity, but rather in her role as wife and mother within her family.

Despite these restrictions, some women were able to accumulate wealth and social status through trade or other entrepreneurial activities. In these cases, they might also be entitled to inherit property and control it independently of their husbands or relatives.

The rights of women in ancient Egypt varied depending on their social class and marital status. Lower-class women had fewer protections and often worked outside the home as laborers or domestic servants. Upper-class women, on the other hand, enjoyed greater privileges, including access to education and personal attendants.

Divorce laws in ancient Egypt were relatively permissive compared to those of neighboring cultures. A woman could initiate a divorce by accusing her husband of impotence, sterility, or desertion. The man also had grounds for divorce if his wife was disobedient or refused to bear children.

A woman’s position within the family and society more broadly depended on her relationship with her father or husband. As such, women’s rights were often tied to those of their male relatives rather than being an independent category of rights.

The legacy of ancient Egyptian women’s legal rights can be seen in later Middle Eastern and Mediterranean societies, where similar patterns of patriarchal authority persisted over time.

The women’s legal rights in Ancient Egypt were relatively advanced compared to other ancient civilizations.

Although they were not equal to men, they enjoyed certain rights and protections under the law.

Marriage was a civil contract that could be entered into by a woman with her consent, although it often took place in her father’s house or through a family arrangement.

In this contract, the wife retained some of her personal property and had the right to manage her own business.

The husband was not necessarily entitled to his wife’s entire estate, and she could retain control over it after divorce or upon her death.

The law also recognized a woman’s right to enter into business contracts, make purchases, and engage in other financial transactions.

Women were considered owners of property, which they could inherit from their relatives, buy, sell, gift, or bequeath as they chose.

The law also recognized a woman’s right to administer her estate after the death of her husband, provided she was not the cause of his demise.

In this case, the wife would manage the joint property and ensure that it passed according to her late husband’s wishes, while still being able to retain some control over her personal property.

It is worth noting that these rights were generally reserved for women of higher social classes and nobility.

Working class women had limited access to the same legal protections and may have been more vulnerable to abuse and exploitation under the law.

The fact remains, however, that in terms of women’s legal rights, ancient Egypt was relatively progressive compared to other civilizations of its time.

List of Rights

- Women could enter into marriage with their consent, and it was considered a civil contract.

- They retained control over their personal property.

- Women had the right to manage their own business and engage in financial transactions.

- The law recognized a woman’s right to administer her estate after the death of her husband, provided she was not the cause of his demise.

- Working-class women had limited access to legal protections.

Important Terms

- Marriage: A civil contract entered into by a woman with her consent.

- Personal property: Property owned by an individual that is separate from their joint property.

- Business contracts: Agreements made between two parties for the sale of goods or services.

- Joint property: Property owned jointly by a couple, often managed by both parties in some capacity.

Punishment and Divorce

Adultery and Infidelity

In ancient Egypt, the concept of adultery and infidelity was viewed as a serious crime that could have significant consequences for all parties involved.

Adultery, or zina in Arabic, referred to sexual relations between a married woman and another man who was not her husband. In contrast, nephew, the term used to describe male adultery, typically denoted illicit relationships with unmarried women.

The legal rights of women in ancient Egyptian society were generally limited. Women had few property rights and could not serve as witnesses or participate in certain religious rituals.

When it came to adultery, however, women were held to a different standard than men. The laws of the Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor, which dates back to around 1800 BCE, stipulated that if a married woman was found to be engaging in adulterous behavior, she could face severe penalties.

The Papyrus Kahun, discovered at the site of El-Lahun, provides further insight into the treatment of adultery and infidelity in ancient Egypt. According to this papyrus, if a married woman engaged in an affair with another man, her husband was entitled to sue for divorce.

Mistress or concubine, as these women were sometimes referred to, had limited rights and could not hold property. However, their relationships with men often provided them with financial security and social status within the community.

The concept of patronage was also significant in ancient Egyptian society. Wealthy patrons would provide support and protection to various individuals or families in exchange for loyalty and services. For women involved in affairs, this patronage could offer a degree of security and social standing.

In conclusion, the legal rights of women in ancient Egypt regarding adultery and infidelity were shaped by societal norms and expectations. While women’s roles were generally limited, the laws governing adulterous behavior reflected a complex and multifaceted understanding of the concept within society.

Punishments for adultery were severe, reflecting societal attitudes towards female infidelity.

Punishments for adultery were indeed severe in ancient Egyptian society, which reflects the strict social norms and patriarchal values that governed women’s lives during this time.

One of the most well-known examples of punishment for adultery is the case of a woman who was accused of having an affair with a temple priest. The woman, named Ta-Shepenwekhu, was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. This harsh sentence highlights the extreme consequences of female infidelity in ancient Egypt.

Another example of punishment for adultery is seen in the Edwin Smith Papyrus, which dates back to around 1600 BCE. The papyrus describes a case where a woman accused her husband of being impotent and having an affair with another man’s wife. However, when questioned by the authorities, the woman herself was found guilty of adultery and sentenced to punishment.

The severity of punishments for female adultery in ancient Egypt can be attributed to several factors, including societal attitudes towards women’s roles and responsibilities. Women were expected to maintain their family’s honor and reputation, while men had greater freedom to engage in extramarital relationships without facing the same level of punishment.

Furthermore, the concept of “family purity” was deeply ingrained in ancient Egyptian society. This meant that a woman’s chastity was seen as essential to maintaining the integrity of her family’s social status and honor. Any breach of this code was considered a serious offense against both the woman herself and her family.

Women’s Legal Rights in Ancient Egypt, however, were not entirely non-existent. While they had limited rights compared to men, women could own property, participate in trade, and even engage in certain professions such as priestesses or healers. Despite these limited rights, women’s lives were still heavily controlled by societal norms and expectations.

In some cases, women were allowed to initiate divorce proceedings if their husband was found guilty of infidelity. However, this rarely occurred in practice due to the strict social norms that governed divorce. Women who initiated divorce proceedings risked being ostracized by their community and losing any potential support or protection from their family.

In conclusion, punishments for adultery were indeed severe in ancient Egyptian society, reflecting the patriarchal values and societal attitudes towards women’s roles and responsibilities. While women had limited rights compared to men, their lives were still heavily controlled by social norms and expectations.

The legal rights of women in ancient Egypt were relatively advanced for its time.

Ancient Egyptian law treated women as equal to men in terms of property ownership and inheritance, a practice that was unique among ancient civilizations.

Women had the right to own and inherit property, including real estate and other valuable items,

and could also engage in trade and commerce on their own behalf.

In addition, women were allowed to participate in religious rituals and ceremonies,

and some even held important priestly roles.

The law of ancient Egypt also protected the rights of women in marriage and divorce.

Women had the right to initiate a divorce and could keep their property and children after a divorce,

although men had greater freedom to remarry after a divorce than did women.

Ancient Egyptian law also allowed women to participate in public life and even held some positions of authority.

Some women served as priestesses, while others served as officials in the government and military.

The most well-known example of an ancient Egyptian woman who held power is Hatshepsut, a female pharaoh who ruled Egypt during the 15th century BC and implemented numerous reforms that helped to modernize the economy and expand trade.

Despite these advancements, women’s rights in ancient Egypt were not without limitations.

Ancient Egyptian society was patriarchal, with men holding greater power and influence than women.

Men had more freedom to engage in public life, participate in politics and hold leadership positions,

while women were generally relegated to the home and family.

The law of ancient Egypt also reflected these social attitudes, with women facing restrictions on their movements and activities outside the home.

Ancient Egyptian law also placed greater burdens on women in terms of childbearing and childcare,

with women expected to bear many children and manage household duties while men focused on external pursuits.

Despite these limitations, the legal rights of women in ancient Egypt were still relatively advanced for its time.

The fact that women could own property, participate in trade and commerce, and engage in public life helped to lay the groundwork for future advancements in women’s rights.

In conclusion, while ancient Egyptian law did not provide absolute equality for men and women,

it did recognize certain rights and privileges for women that were unique among ancient civilizations.

Women’s legal rights in ancient Egypt were relatively advanced compared to other civilizations during that time period. While they had some limitations, women enjoyed a higher level of freedom and respect than their counterparts in many other cultures.

The Code of Hammurabi, which was enacted in Babylon around 1754 BC, did not apply in Egypt, but the Edict of Horemheb, issued by Pharaoh Horemheb in around 1323 BC, contained provisions that protected women’s rights. This edict prohibited the practice of selling or giving away daughters as wives, and it also required that widows be given a share of their husband’s property.

The laws governing marriage in ancient Egypt were complex and often varied depending on social class. Women from wealthy families could enter into marriages with men of lower social status, but this was not common among the lower classes. The practice of marriage by capture, where a woman would be taken as a wife without her consent, was also known to occur.

Divorce laws in ancient Egypt were relatively relaxed, and women had some rights in the event of divorce. If a husband died, his widow could choose whether or not to remarry, but if she did remarry, she would lose any property that she had received from her first husband. If a woman divorced her husband without just cause, she would also be required to return any property that she had received during the marriage.

Property rights for women in ancient Egypt were limited, and they generally only inherited property if their husbands died childless or left no other heirs. Women could own land and engage in business dealings, but these activities were often subject to the control of male relatives or guardians.

The worship of female deities was widespread in ancient Egyptian society, with many women serving as priestesses and participating in sacred rituals. The goddess Isis, in particular, was revered for her role as a protector and caregiver, and she was often invoked by women seeking help and guidance.

Some notable examples of powerful women from ancient Egypt include Hatshepsut, who ruled as pharaoh from around 1479 to 1458 BC; Nefertiti, the queen of Pharaoh Akhenaten; and Cleopatra VII, who ruled from 51 BC until her death in 30 BC.

Women’s roles in ancient Egyptian society were not limited to the home or the temple. Many women worked as craftsmen, merchants, and traders, and some even rose to positions of power and influence within the government.

In summary, while women in ancient Egypt faced some limitations and challenges, they enjoyed a relatively high level of freedom and respect compared to other cultures during that time period. The worship of female deities was widespread, and many women held important roles in society, including as rulers, priestesses, craftsmen, and traders.

The legacy of women’s rights in ancient Egypt can be seen in the modern-day movement for women’s empowerment and equality. Many women today draw inspiration from the strong and independent female figures of ancient Egyptian history, who paved the way for future generations of women to break free from patriarchal norms and achieve their goals.

Some key statistics and facts about women’s rights in ancient Egypt include:

- The Edict of Horemheb prohibited the practice of selling or giving away daughters as wives.

- Women could own land and engage in business dealings, but these activities were often subject to the control of male relatives or guardians.

- The worship of female deities was widespread in ancient Egyptian society, with many women serving as priestesses and participating in sacred rituals.

- Some notable examples of powerful women from ancient Egypt include Hatshepsut, Nefertiti, and Cleopatra VII.

Key milestones in the development of women’s rights in ancient Egypt include:

- The Edict of Horemheb (around 1323 BC), which protected women’s rights and prohibited certain practices.

- The rise to power of Hatshepsut (around 1479-1458 BC), who ruled as pharaoh and expanded women’s roles in society.

Some key figures in the history of women’s rights in ancient Egypt include:

- Hatshepsut, who ruled as pharaoh and expanded women’s roles in society.

- Nefertiti, the queen of Pharaoh Akhenaten.

- Cleopatra VII, who ruled from 51 BC until her death in 30 BC.

Divorced women could remarry, but might face difficulties.

In ancient Egyptian society, divorced women had the option to remarry, which was seen as a way for them to regain their status and social position.

The legal rights of divorced women in ancient Egypt were somewhat restricted compared to those of men, however. According to the laws of the time, a woman’s ability to remarry was largely dependent on her social class and economic situation.

Women from lower-class backgrounds often had limited opportunities for remarriage due to their lack of financial resources and social connections.

On the other hand, women from higher-class backgrounds may have had more options available to them, such as marrying into a family with wealth and influence. However, even in these cases, the woman’s marriage was often seen as an economic arrangement rather than a love match.

The law allowed for the remarriage of divorced women after a specified period of time had elapsed since their previous divorce. The duration of this waiting period varied depending on the circumstances of the divorce and the social status of the parties involved.

In general, however, it was more difficult for divorced women to remarry than it was for men who had been divorced by their wives. Men were often able to secure new wives relatively quickly after a divorce, particularly if they were from a higher-class background.

It’s worth noting that these legal restrictions on remarriage applied not just to divorced women but also to other categories of women in ancient Egyptian society. For example, widows and single women may have faced similar challenges when seeking remarriage, often due to societal pressure to marry into a family with wealth and influence.

Overall, while the law in ancient Egypt allowed for the possibility of remarriage by divorced women, it also imposed significant restrictions on their ability to do so. These restrictions were largely driven by social class and economic considerations rather than any explicit concern for the rights or interests of women themselves.

Laws on divorce varied depending on circumstances and social status.

The laws governing divorce in ancient civilizations often varied significantly based on the social status of the individuals involved, as well as specific circumstances.

In ancient societies like Greece and Rome, for instance, property rights played a crucial role in determining the outcome of divorces, with women’s ability to initiate or participate in divorce proceedings often heavily limited due to their inferior status under the law.

Ancient Egypt, however, presents an interesting case study regarding women’s legal rights, particularly in the context of divorce. Despite the predominantly patriarchal nature of Egyptian society during that period, there is evidence to suggest that women enjoyed relatively greater autonomy and legal protections compared to other ancient civilizations.

The Papyrus Harris, a significant historical text, contains provisions related to marriage and divorce. It stipulates that marriages could be terminated by mutual consent or through the intervention of a third party in cases where either spouse was found guilty of adultery.

One notable aspect of Egyptian divorce law is the concept of “talaq,” which refers to the right of a husband to unilaterally dissolve his marriage without providing grounds for doing so. However, it’s worth noting that this right could also be granted to women in specific circumstances, such as when they were abandoned by their husbands or suffered physical abuse.

Moreover, the Edict of Khumbanigash II from Babylonian law codifies provisions related to marriage and divorce. According to its stipulations, a woman’s decision to initiate a divorce could be facilitated if her husband was guilty of marital incompatibility, impotence, or other serious transgressions.

In several ancient civilizations, including the Babylonians, Greeks, and Romans, women’s rights in the context of marriage and divorce were often tied to their social status. While these laws varied across cultures, there are instances where women enjoyed more significant protections and autonomy compared to others.

As mentioned earlier, ancient Egyptian law provided women with some level of protection in cases of marital disputes or abandonment. In contrast, the Babylonian marriage contract from the 6th century BCE explicitly granted a wife the right to initiate divorce proceedings if her husband failed to provide for her material needs or subjected her to physical abuse.

It is worth noting that while these historical documents reveal an inclination towards recognizing women’s rights within certain contexts, their practical application was often subject to social norms and limitations. As such, the legal frameworks governing marriage and divorce in ancient societies reflect a complex interplay between patriarchal structures, evolving social attitudes, and the specific needs and circumstances of individuals.

The legal rights of women in ancient Egypt were complex and multifaceted, reflecting the social and economic conditions of the time. Although they had certain privileges, their status was generally inferior to that of men.

The ancient Egyptian society was patriarchal, with the pharaoh holding absolute power and authority. The male-dominated society placed a strong emphasis on masculinity and the importance of women’s roles in the family and household.

Despite these limitations, women in ancient Egypt had some legal rights. Sistra (women) had the right to own property, including land and goods, and could engage in commercial activities such as trading and banking.

The Code of Hammurabi, which was adopted by the Egyptians during the New Kingdom period, provided women with some protection under the law. Article 130 of the code states that if a man’s wife is injured or killed, he must pay damages to her family or relatives.

Women also had the right to initiate divorce proceedings in ancient Egypt. While men had absolute power over their wives, a woman could petition for divorce if she was subjected to physical abuse or mistreatment by her husband.

The practice of uxorilocal marriage, where a man would move to his wife’s family home after marriage, was also prevalent in ancient Egypt. This social arrangement allowed women to maintain control over their families’ property and economic resources.

However, the rights of women in ancient Egypt were often curtailed by societal expectations and customs. Women’s roles were largely limited to managing household affairs, raising children, and participating in domestic activities such as spinning, weaving, and cooking.